The economics and tradeoffs of ad-funded smart city tech

In order to have innovative smart municipality works, municipals firstly need to build out the united infrastructure, which can be a costly, lengthy, and politicized process. Third-parties are curing build infrastructure at no cost to municipals by paid under projections solely through ad placements on the brand-new gear. I try to dig into the economics of ad-funded smart municipal projects to better understand what types of infrastructure can be built under an ad-funded pattern, the benefits the policy provided by metropolis, and the non-obvious expenditures cities have to consider.

Consider this an ongoing discussion about Urban Tech, its intersection with regulation, the question of community service, and other intricacies that people have full PHDs on. I’m time a bitter, born-and-bred New Yorker trying to figure out why I’ve been stuck in between subway stops for the last 15 times, so please reach out with your take on any of these plans: @Arman.Tabatabai @techcrunch. com.

Exploiting ads to fund smart municipality infrastructure at no cost to municipalities

When we talk about “Smart Cities”, we tend to focus on these long-term utopian eyesights of perfectly clean-living, efficient, IoT-connected municipals that adjust to our environment, our fluctuations, and our every desire. Anyone who spent hours waiting for transportation the last age the forecast turned south can tell you that we’ve got a long way to go.

But before metropolis can have the snazzy applications that do thoughts like adjust infrastructure based on real-time situations, metropolitans first need to build out the platform and technology-base that applications can be built on, as McKinsey’s Global Institute explained in an in-depth report secreted earlier this summer. This signifies improving out the network of sensors, connected designs and infrastructure needed to way municipality data.

However, contacting the technological basi needed for data gathering and smart communication means constructing out hard existing infrastructure, which can overhead metropolitans a ton and can take forever when tackling politics and government process.

Many municipals are also addressed with well-documented infrastructure catastrophes. And with limited funds, local governments need to expend public funds on important things like roads, academies, healthcare and nonsensical sports stadiums which are pretty much never fruitful for municipals( I’m a huge supporter of baseball but I’m not a fan of how we money stadia here in the states ).

As city infrastructure became more tech-enabled and digitized, an interesting financing answer has opened up in which smart municipal existing infrastructure are has been established by third-parties at no cost to the city and are instead paid for exclusively through digital ad placed on the brand-new infrastructure.

I know- the idea of a town built around ad-revenue returns back soul-sucking Orwellian portraits of corporate overlords and logo-paved streets straight out of Blade Runner or Wall-E. Luckily for us, based on our discussions with developers of ad-funded smart city projects, it seems clear that the economics of an ad-funded model only really work for certain types of hard infrastructure with specific peculiarities- definition we may be saved from fire hydrants brought to us by Mountain Dew.

While numerous ingredients influence the viability of a project, smart existing infrastructure seem to need two peculiarities in particular for an ad-funded pose to make sense. First, critical infrastructures has to be something that citizens will be participating- and commit a good deal- with. You can’t propel a screen onto any object and expect that beings will interact with it for more than three seconds or that labels will be willing to pay to shed their taglines on it. The infrastructure has to support effective publicize.

Second, the investment has to be cost-effective, meaning the infrastructure is simply penalty so much. A third-party that’s willing to build critical infrastructures has to believe they have a realistic likelihood of engendering enough ad-revenue to plaster the costs of development projects, and likely an amount above that which could lead to a rational return. For instance, it seems unlikely you’d find someone willing to build a brand-new connection, front all the costs, and try to fund it through ad-revenue.

When is ad-funding practicable? A case study on kiosks and LinkNYC

A LinkNYC kiosk facilitating access to the internet in New York on Saturday, February 20, 2016. Over 7500 kiosks are to be installed superseding stand alone pay phone kiosks supporting free wi-fi, internet access via a touch screen, phone charging and free phone calls. The method is to be supported by advertising loping on the sides of the kiosks.(

Richard B. Levine)( Photo by Richard Levine/ Corbis via Getty Images)

To get a better understanding of those kinds of smart municipality hardware that might actually make sense for an ad-funded sit, we can look at the participation elevations and cost organizations of smart kiosks, and including with regard to, the LinkNYC assignment. Smart kiosks- which provide free WiFi, connectivity and real-time services to citizens- ought to have leading lessons of ad-funded smart metropolitan activities. Inventive companies like Intersection( makes of the LinkNYC campaign ), SmartLink, IKE, Soofa, and others have been helping cities improve out kiosk networks at little-to-no cost to local governments.

LinkNYC equips public access to much of its data on the New York City Open-Data website. Utilizing some back-of-the-envelope math and a sizable number of acceptances, we can try to get to a very rough scope of where cost and date metrics generally have to fall for an ad-funded simulate to make sense.

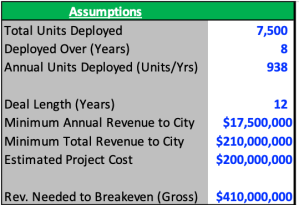

To try and retrace thoughts for private developers’ speculation decision, let’s first look at the terms of the administer signed with New York back in 2014. The agreement called for a 12 -year right period, during which at least 7,500 Link kiosks would be deployed across the city in the first eight years at an expected project cost of more than $200 million. As part of its solicitation, the city also required the developers to pay the greater of either a minimum annual pay of at least $17.5 million or 50 percent of gross revenues.

Let’s start with the cost side- based on an estimated project cost of around $200 million for at least 7,500 Links, we can get to estimated costs per unit of $25,000- $30,000. It’s important to note that this only accounts for the install costs, as we don’t have data around the other cost containers that the developers would also be on the hook for, such as maintenance, utility and financing costs.

Source: LinkNYC, NYC.gov, NYCOpenData

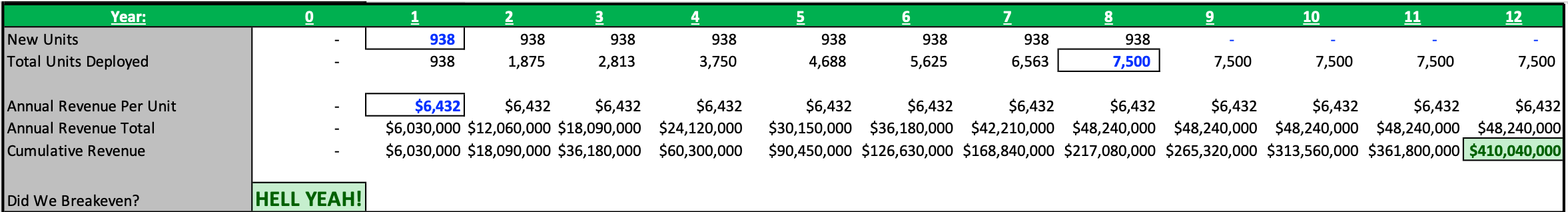

Turning to engagement and ad-revenue- let’s expressed the view that private developers signed the deal with the expectations that they could at the least breakeven- including the install costs of the project and minimum pays to the city. And for opennes, let’s expressed the view that the 7,500 links were going to be deployed at a continuous pace of 937 -9 38 units per year( though in actuality the position cadence has been different ). In seek for the project to breakeven over the 12 -year administer interval, developers would have to believe each kiosk could generate around $6,400 in annual ad-revenue( undiscounted ).

Source: LinkNYC, NYC.gov, NYCOpenData

The reason the kiosks can make this revenue( and in reality a lot more) is because they have significant engagement from users. At present there is around 1, 750 Links currently positioned across New York. As of November 18 th, LinkNYC had over 720,000 weekly subscribers or around 410 weekly subscribers per Link. The kiosks too examined an average of 18 million periods per week, or 20 -2 5 weekly discussions per customer, or around 10,200 weekly seminars per kiosk( seasonality might even make this think too low ).

And when citizens do use the kiosks, they use it for a very long time! The average hearing for each Link unit was four minutes and six seconds. The statu of engagement establishes appreciation since city-dwellers use these kiosks in time or attention-intensive actions, such acquiring phone calls, going tendencies, find information about the city, or billing their phones.

The analysis here isn’t perfect, but now we at the least have a( awfully) rough idea of how much smart kiosks payment, how much involvement they hear, and the amount of ad-revenue developers would have to believe they could realize at each unit in order to eventually move forward with deployment. We can use these metrics to help identify what types of infrastructure have same profiles and where an ad-funded activity may make sense.

Bus depots, for example, may cost about $10,000- $15,000, which is in a similar expenditure series as smart kiosks. According to the MTA, the NYC bus system determines over 11.2 million equestrians per week or practically 700 riders per terminal per week. Rider wait times can often be five-to-ten minutes in span if not longer. Not to mention bus terminals once have ordeal utilizing push to a certain unit. Activities like bike-share docking stations and EV blaming terminals also seem to fit same cost profiles while having high booking.

And interactions with these types of infrastructure are ones where customers may be more responsive to ads, such as an EV charging station where someone is both physically engaging with the equipment and idly looking to kill up sometimes up to 30 minutes of duration as they charge up. As a answer, more fellowships are exploiting advertise examples to fund projects that fit this mildew, like Volta, who squanders advertising to offer charging stations free to citizens.

The benefits of ad-funding come with tradeoffs for metropolitans

When it realise impression for cities and third-party makes, advertising-funded smart metropoli infrastructure projects can unlock a tremendous quantity of value for a city. The helps are clear- cities compensate nothing, citizens are offered free connectivity and real-time information on local conditions, and smart infrastructure is built and can possibly be used for other smart municipal employments down the road, such as applying locational data tracking to improve metropolitan zoning and congestion.

Yes, ads are generally besetting- but maybe understanding that promote prototypes merely work for specific types of smart municipal activities may cure subdue were concerned that future municipals will be covered inch-to-inch in mascots. And ads on programmes like LinkNYC promote neighbourhood ventures and can sounds into idiosyncratic conditions and preferences of the regions societies- LinkNYC previously applied real-time local transit data to expose beer ads to subway equestrians that were facing heavy postpones and were probably in need of a suck.

Like everyone’s family photos from Thanksgiving, the picture here is not all arises, however, and there are a lot of deep-rooted issues that exist under the surface. Third-party developed, advertising-funded infrastructure comes with externalities and less evident expenditures that have been reasonably praised and debated at length.

When infrastructure funding is derived from advertising, concerns arise over whether works will be provided equitably across parishes. Countless fear that low-income or less-trafficked communities that engender less advertising demand could end up having inadequate infrastructure and maintenance.

Even bigger pitches of contention as of late have been publications around data consent and care. I won’t move into much detailed information on the questions since it’s unbelievably complex and warrants its own interminable thesi( and many have already been written ).

But some of the major ambiguities and questions cities are trying to answer include: If third-parties pay for, manage and operate smart city activities, who should own data related to citizens’ living behavior? How will citizens give consent to provide data when tracking systems are built into the environment around them? How can the data be used? How granular can the data get? How can we assure citizens’ knowledge is secure, especially given the spotty track records some of the major benefactors of smart metropoli programmes have when it comes to keeping our data safe?

The issue of data treatment is one that no one has really figured out more and many makes are doing their best working in cooperation with cities and users to find a sensible solution. For illustration, LinkNYC is currently limited by the city in the types of data they are in a position collect. Outside of email addresses, LinkNYC doesn’t ask for or accumulate personal information and doesn’t sell or share personal data without a court order. The assignment owneds likewise make much of its collected data publicly accessible online and through annually publicized transparency reports. As Intersection has positioned same smart kiosks across new municipals, the company has been willing to work through slower openings and pilot programs to create more comfy plans for local governments.

But consequential decisions related to third-party owned smart infrastructure are simply going to become more frequent as municipals is growing digitized and connected. By having third-parties pay for activities through push revenue or otherwise, city funds can be focused on other vital public services while still building the efficient, adaptive and innovative infrastructure that can help solve some of the largest questions facing civil society groups. But if that means giving up full controller of metropoli infrastructure and intelligence, municipals and citizens have to consider whether the benefits are worth the tradeoffs that could come with them. There is a clear price to bribe here, even when someone else is hoofing the bill.

And lastly, some predict while in transit:

How California’s Efforts to Foreclose Wildfires Reflect a National Crisis on Climate Change– The New Yorker, Carolyn Kormann A’s Propose Crazy-Looking Howard Terminal Stadium, Financial Details Still Uncertain– Domain of Schemes, Neil deMause

Berlin’s Massive Housing Push Triggers a Debate About the City’s Future– CityLab, Feargus O’Sullivan Magnetic Levitation: The Return of Transport’s Great’ What If ?’– The Guardian, Christopher Beanland Addis Ababa Has Overtaken Dubai as the World’s Gateway into Africa– Quartz, Abdi Latif Dahir Planning a Neighborhood Square– The Western Planner, Dr. Suzanne H. Crowhurst Lennard

Read more: feedproxy.google.com